In Defense of SaaS

Microsoft is in a 26% drawdown. Oracle has been cut in half. Salesforce is getting demolished. Adobe, ServiceNow, Palantir - all taken to the woodshed. The software sector ETF (IGV) has plunged 28% from its September peak, and $285 billion in market cap has evaporated in a matter of weeks. Traders at Jefferies are calling it the “SaaSpocalypse.”

The thesis driving the selloff is seductively simple: AI coding tools like Claude Code and Codex have made it so easy to build software that the value of all these companies is headed toward zero. You can vibe-code something that looks like Salesforce over a weekend. Therefore Salesforce is dead.

Matt Shumer’s “Something Big Is Happening” post went viral this week - 5 million views and counting - arguing that AI is transforming everything and most people aren’t paying close enough attention. He’s right. But somewhere between “AI is transformative” and “sell all software,” the logic breaks down. The market heard “AI changes everything” and concluded “therefore software is worthless.” That’s a non sequitur. The entire point of Shumer’s piece is that people should be using these AI tools seriously - and the tools they should be using are, well, SaaS products with paid subscriptions.

— Matt Shumer (@mattshumer_) February 10, 2026

I think this is one of the biggest overcorrections happening in public markets right now. And I think the logic underpinning it is a textbook case of reductionism - mistaking one ingredient for the whole meal.

You can clone the interface. You can’t clone the business.

Yes, you can now build something that looks like Reddit in a weekend. Congratulations. How are you going to get 100 million people a day to use it? How are you going to spend a decade perfecting the recommendation algorithm? How are you going to build the moderator ecosystem, the community culture, the API integrations, the advertiser relationships, the brand safety infrastructure?

You can build something that looks like Salesforce. But Salesforce isn’t a CRM interface. It’s a decade of customer data, thousands of AppExchange integrations, an entire ecosystem of consultants and admins who’ve built their careers on the platform, and the hard-won trust of procurement departments at every Fortune 500 company on earth.

The vibe-coding thesis confuses the way software looks with the way software works inside an organization.

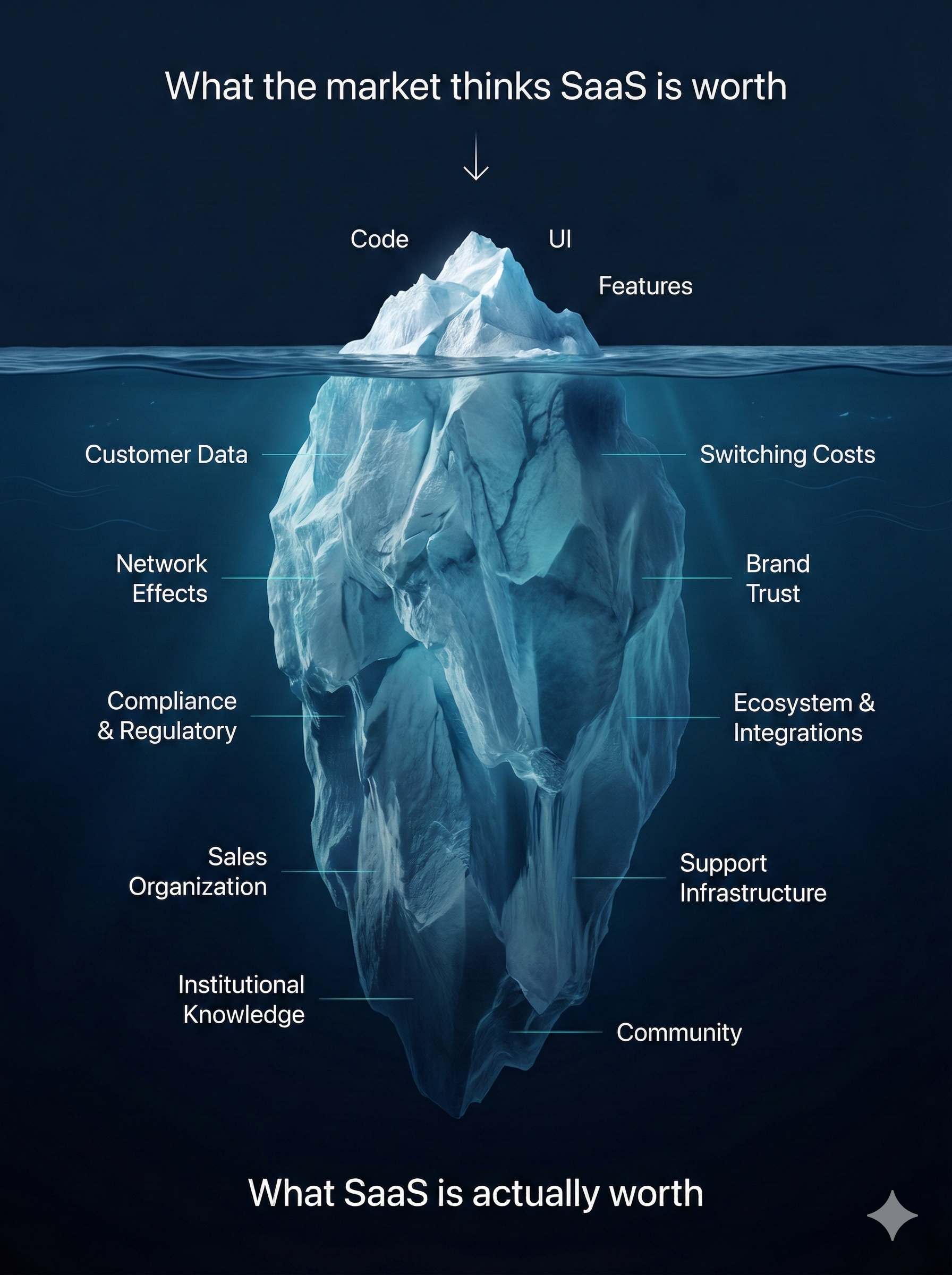

What actually makes SaaS valuable?

Let’s actually enumerate the moats that public SaaS companies tend to possess - because the market seems to have forgotten they exist:

Network effects. Every company on Slack makes Slack more valuable. Every developer on GitHub makes GitHub more valuable. Every sales team on Salesforce generates data that trains the models that help the next sales team.

Switching costs. Ripping out your ERP system is not like switching from one note-taking app to another. ServiceNow implementations can take 12-18 months. Workday migrations are multi-year projects. The switching cost isn’t the software license - it’s the organizational upheaval.

Data moats. Years of proprietary customer data, workflow data, and interaction data can’t be replicated by spinning up a new app. The data is the product for many of these companies. Bloomberg Terminal isn’t expensive because the UI is hard to build.

Brand and trust. When a CISO is deciding which cybersecurity platform to deploy across a 50,000-person enterprise, they’re not going to pick totallylegitsecurity.ai that was registered an hour ago. They’re going to pick CrowdStrike or Palo Alto Networks because their job is on the line. Enterprise software purchasing is fundamentally a trust transaction.

Regulatory and compliance infrastructure. SOC 2, HIPAA, FedRAMP, GDPR - years of compliance investment that a weekend vibe-coding project doesn’t have and can’t fake.

Now ask yourself: how many public SaaS companies actually look like a simple point solution with no switching costs, no data moat, and no network effects? Very few. The ones that do were already in trouble before AI coding tools existed.

And yes, some of the price correction is deserved. A startup called Base44 went viral recently for canceling $350K a year in Salesforce licenses after vibe-coding a replacement. And honestly? $350K a year for a CRM is a rip-off. But here’s the thing people miss about that story: Salesforce has been overpriced and under threat for years. HubSpot, Pipedrive, Close - there’s been a cheaper, more modern CRM alternative available every single year for the past decade. And yet Salesforce just keeps winning. Not because the software is better. Not because the price is fair. Because switching your CRM means retraining your entire sales org, migrating years of pipeline data, rebuilding every integration, and praying nothing breaks. Base44 isn’t the beginning of the end for Salesforce. It’s the latest in a long line of companies discovering what Salesforce’s churned customers already know: the hard part isn’t building the replacement. It’s surviving the migration.

If your features are your moat, you’ve always been in a race

Here’s the thing: if the only thing standing between you and your competitors was that your features were slightly better, you were already in a commodity race. AI coding tools don’t change the fundamental dynamic - they just accelerate the clock speed.

But here’s what people miss: that race is now one that everyone runs at exactly the same speed. If your competitor can vibe-code a clone of your feature in a weekend, you can vibe-code a clone of their next feature in a weekend too. AI is a symmetric weapon. It doesn’t selectively advantage attackers over incumbents.

In fact, it arguably advantages incumbents more. They have the existing user base, the distribution, the data, and the brand. They can ship AI-powered features to millions of users overnight. A startup with a weekend project still needs to acquire every single customer from scratch.

Startups aren’t dead either

To be clear, I’m not just defending the incumbents here. I’m defending the entire category. Because the other half of the SaaSpocalypse thesis - that new SaaS startups are pointless because anyone can build anything now - is equally wrong.

Yes, the barrier to building software has dropped. But the barrier to having a good idea hasn’t dropped at all. The barrier to understanding an underserved market, identifying a workflow that’s broken, and designing a genuinely better approach - none of that got easier because Claude can write code faster.

And here’s the thing about incumbents: they can’t change their product every day. They have millions of users who depend on the existing interface, the existing workflow, the existing mental model. Every significant change risks confusing or alienating the installed base. This is the innovator’s dilemma, and AI coding tools don’t solve it - they might even make it worse, because the temptation to ship faster can conflict with the need for product stability.

Startups have always won by finding the gaps that incumbents can’t close without breaking what already works. Slack didn’t beat email by being easier to code - it won by reimagining how teams communicate. Figma didn’t beat Adobe by writing faster code - it won by rethinking collaboration. The next generation of great SaaS companies will do the same. They’ll use AI to build faster, sure. But the insight about what to build will still be the hard part, and that insight will still be rare and valuable.

The SaaSpocalypse thesis somehow manages to be simultaneously too bearish on incumbents and too bearish on startups. It says incumbents are doomed because their code can be replicated, while also saying startups are pointless because code is cheap. But if code is cheap for everyone, then the companies that win - whether incumbents or startups - will be the ones that are great at everything except the code.

The Pollan parallel: nutritionism for software

There’s a remarkable parallel here to Michael Pollan’s In Defense of Food. Pollan argued that the food industry had been captured by “nutritionism” - the reductive ideology that food is nothing more than the sum of its nutrient parts. Under this framework, a fortified Pop-Tart with added vitamins is equivalent to a home-cooked meal, because the nutrients are the same.

The SaaSpocalypse thesis is nutritionism for software. It reduces the value of a SaaS company to a single nutrient: how long did the code take to write? Under this framework, if AI can write the code faster, the company is worthless.

But good software, like good food, is so much more than its ingredients. It’s the years of customer feedback baked into product decisions. It’s the institutional knowledge of how procurement works at a hospital system. It’s the 14,000-person sales organization that knows how to land and expand in the enterprise. It’s the ecosystem of partners, integrators, and developers. It’s the compliance certifications. It’s the brand trust. It’s the community.

Pollan’s thesis was that real food - the sort your great-grandmother would recognize - didn’t need to be defended on nutritional merits because it was a complex, evolved system that couldn’t be reduced to a list of vitamins. Real SaaS businesses are the same. They are complex, evolved systems that can’t be reduced to the number of lines of code it takes to replicate their UI.

Pollan’s advice was: Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.

My advice is: Buy SaaS. Not overpriced. Mostly moats.

Nobody ever got fired for buying Salesforce

There’s a fundamental truth about enterprise software purchasing that the SaaSpocalypse thesis completely ignores: when you buy software for your company, you’re not just buying features. You’re buying someone to blame when things go wrong.

You don’t always pick the cheapest option. You don’t always pick the most innovative option. You pick the option that, if it fails, you can defend to your boss. “We went with Salesforce” is a defensible sentence in any boardroom in America. “We went with an app I vibe-coded over the weekend” is a resignation letter.

This is the same dynamic that kept IBM dominant for decades and that keeps McKinsey and Deloitte in business despite armies of cheaper, often smarter competitors. Enterprise buyers optimize for career risk, not unit cost. They want a vendor that will still exist in three years, that has a support team they can call at 2am, that has a track record of not losing their data.

And here’s the counterintuitive kicker: the proliferation of AI-built software might actually accelerate consolidation toward the big established players rather than eroding their market share. When every weekend project and every startup can spin up a SaaS tool, the market doesn’t get disrupted - it gets noisy. And when the market gets noisy, buyers retreat to the names they trust.

This is the paradox of choice applied to software. Barry Schwartz showed decades ago that more options don’t make consumers happier or more adventurous - they make them more anxious and more likely to default to the safe, familiar pick. If the SaaSpocalypse thesis is right and a thousand new AI-built CRMs flood the market, the most likely outcome isn’t that Salesforce loses customers. It’s that the confused, overwhelmed buyer clings even harder to the brand they already know.

The agent objection

“But agents will change everything! In the future, AI agents will pick the software, and they won’t have brand loyalty!”

Will they, though? Let’s think about what a competent AI agent actually optimizes for when selecting enterprise software. It’s going to evaluate reliability, uptime history, security certifications, integration breadth, data migration complexity, vendor stability, and total cost of ownership including switching costs.

In other words, an AI agent evaluating software vendors is going to be more rational than a human buyer - which means it’s going to be more biased toward established, trusted incumbents, not less. The agent isn’t going to get seduced by a slick landing page from a company that was incorporated last Tuesday. It’s going to look at the five-year uptime record, the SOC 2 Type II report, and the 4,000 reviews on G2.

Agents don’t eliminate switching costs. If anything, they’ll quantify them more precisely - and route away from risky switches.

“But what if the UI just… goes away?”

There’s a more radical version of the agent argument that deserves its own treatment, because it’s not entirely wrong: the idea that software interfaces themselves are becoming obsolete. In this vision, you don’t use Salesforce - you tell your AI agent to manage your pipeline, and it figures out the rest. No dashboard. No login screen. No per-seat subscription. The UI vanishes entirely, replaced by a conversational layer that orchestrates everything underneath.

Let’s take this seriously, because there’s a real kernel of truth here. A lot of enterprise software is bad UI wrapped around a simple database operation. If an agent can just do the thing - update the CRM, file the expense report, schedule the meeting - without making you navigate seven tabs and three dropdown menus, that’s a genuine improvement. Some SaaS interfaces are, frankly, tax on human attention that exists only because we didn’t have a better way to talk to computers. Those interfaces should go away.

But here’s what the “death of UI” crowd consistently gets wrong: they confuse the interface with the infrastructure.

When your agent “manages your pipeline,” it still needs to store that data somewhere reliable, keep it secure, sync it across your team, enforce your access controls, integrate with your billing system, and comply with your industry’s regulations. That’s not a UI problem - that’s a platform problem. And the platform doesn’t go away just because the interface changes.

In fact, this future might be better for the best SaaS companies, not worse. If agents become the primary way humans interact with software, then the companies that win are the ones with the best APIs, the most reliable infrastructure, the deepest integrations, and the most trusted data layer. That’s a description of the SaaS incumbents, not a description of a weekend project.

Think of it this way: the rise of mobile didn’t kill software companies - it just changed the interface from desktop to phone. The rise of cloud didn’t kill software companies - it changed the delivery model from on-prem to browser. If agents become the next interface layer, the software underneath still needs to exist, still needs to be maintained, and still needs to be trusted. Someone still needs to be the system of record. Someone still needs to pick up the phone when the data doesn’t sync.

The UI might change. The value doesn’t.

The BofA paradox

Bank of America’s Vivek Arya made a sharp observation about the current selloff: investors are simultaneously pricing in two mutually exclusive scenarios. Either AI capex is deteriorating to the point that it won’t deliver ROI (bad for the AI thesis), or AI is so powerful that it will destroy all software companies (bad for SaaS). Both can’t be true at the same time. If AI is powerful enough to destroy SaaS, then the companies building AI infrastructure are going to see massive returns. If AI infrastructure spending won’t pay off, then AI isn’t actually powerful enough to destroy SaaS.

The market is in a fog of fear, and fear doesn’t do nuance.

What’s actually at risk

I’m not arguing that nothing changes. Some things clearly do:

Per-seat pricing is under pressure. If 10 AI agents can do the work of 100 sales reps, you don’t need 100 Salesforce seats. But smart SaaS companies are already pivoting to usage-based and outcome-based pricing. The revenue model adapts. The underlying value of the platform doesn’t disappear.

Thin point solutions without differentiation are vulnerable. If your entire product is a simple workflow that can be replicated in a few prompts, yes, you have a problem. But this has always been true - the threat was just “a larger competitor adds your feature” rather than “a weekend coder replicates your feature.”

The growth premium is compressing. Markets are right to reassess multiples. But reassessing multiples is very different from pricing in extinction.

The bottom line

The SaaSpocalypse narrative treats software companies as if they are nothing more than bundles of code. They’re not. They’re networks of customers, ecosystems of integrations, reservoirs of proprietary data, and repositories of institutional trust - all wrapped in code that happens to be the least defensible part of the whole package.

The market is pricing in a world where the ability to write code fast makes everything else irrelevant. That’s like saying the ability to cook rice fast makes a Michelin-star restaurant irrelevant. The cooking was never the hard part.

The hard part was - and remains - figuring out what to build, convincing people to use it, earning their trust over years, and building an ecosystem so deep that leaving feels like moving out of your house.

Some SaaS companies will be disrupted. The ones that were already commodities. But the great ones - the ones with real moats - just got access to the same AI tools as everyone else. They’ll use them to build faster, serve better, and widen their lead.

Sell the panic. I’ll buy the moats.

Note: This post reflects my personal views and is not investment advice. I may hold positions in companies mentioned.